Interview with painter Lily Simonson

I don’t remember the first time I saw Lily Simonson’s work but I think I heard about her paintings of the deep sea on a podcast. After hearing them being described, I just had to see the images and they blew me away!

Tell us a little bit about yourself, your name and what do you do?

I’m Lily Simonson and I’m an artist who paints at the most remote reaches of the planet–Antarctica and the deep sea.

Have you always been artistic? Why or why not?

I have always made drawings and paintings, and always used the ocean and sea creatures as subject matter!

What materials do you use to create your artwork? Is there a certain material you prefer?

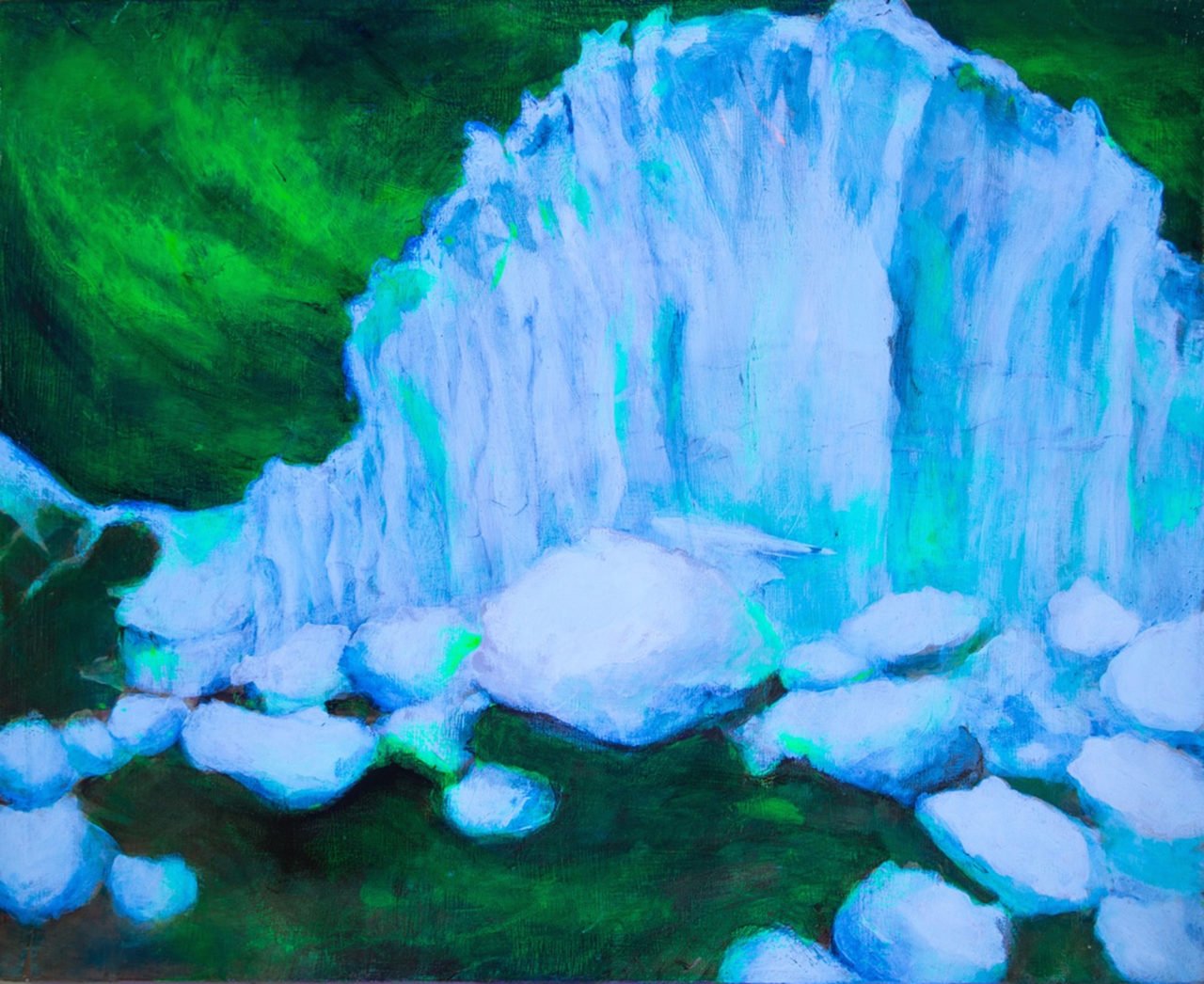

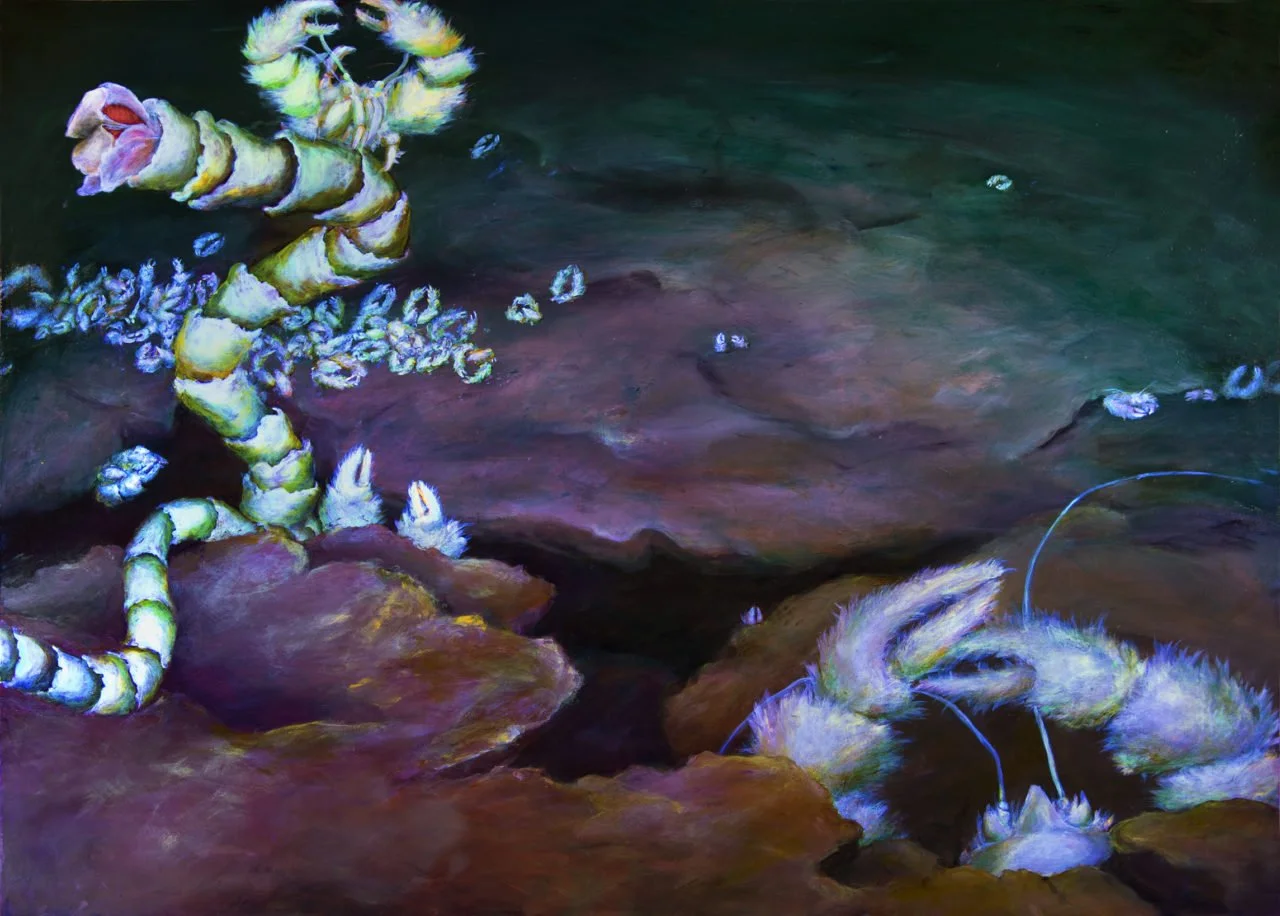

I use lots of thin glazes, inspired by the techniques of renaissance painting. But for the top layer, I use fluorescent pigments that glow under ultraviolet light, amplifying the luminous qualities of my subjects. It also evokes the aesthetics of 1960s psychedelia and in turn, highlights the hallucinatory qualities of the alien-like worlds that I paint.

Was there some or something that impacted your decision in creating artwork centered around/about science?

When I was in graduate school I became focused on a single muse–the (then) newly-discovered yeti crab. It became the subject of dozens of paintings. It is a white squat lobster with pincers covered in this mammal-like fur, or setae. Yeti crabs are found at deep-sea hydrothermal vents and seeps in chemosynthetic communities–ecosystems where organisms live without light or photosynthesis. It’s this parallel world, in which the yeti crab lives off of eating microbes, which in turn live off of sulfur and methane. I became fascinated by this incredible process of chemosynthesis–turning chemicals into energy and began painting other creatures who live in the deep sea, without light, in these magical-seeming ecosystems.

I work directly from life, so to access models for my work, I began borrowing specimens from scientific laboratories. Eventually, I built a relationship with these scientists and they began inviting me to join them on deep-sea research expeditions, where I got to paint the organisms as they were collected from the ocean’s depths. Through my work with deep-sea scientists, I got introduced to the incredible marine environment in the Antarctic Ocean. I began to seek out Antarctic subjects as well and completed two residencies in Antarctica, camping and painting at remote field sites and scuba diving under the sea ice. Like the deep sea, Antarctica is extremely distant from most human life and yet extremely vulnerable to the impacts of human-induced climate change.

These sites have emerged in my work as emblems of nature’s glory and vulnerability. They are areas that remain obscure to most and are often perceived as barren. Yet they are teeming with the most extraordinary organisms and natural features you could ever imagine. I want my paintings to contribute to the dialogue of contemporary art, but also to inspire environmental stewardship amongst my viewers. And to change the way we think about ourselves in relationship to the natural world.

Also, painting these novel discoveries tied me to the lineage of artists-naturalists, who explored and research the Americas and used painting to share “newly-discovered” organisms with the public. But actually, those organisms were new only to European eyes; people indigenous to the “new world” were well-acquainted with most of the organisms described by Audubon and his cohort. But the Antarctic and the deep sea, below the area reached by light, are spaces that humans of any kind of only just begun to access. So it feels truly novel, and represents the vanguard of human knowledge.

What is something weird or funny you have encountered?

The funniest weirdest thing is that one of the yeti crab species (kiwa puravida) dances constantly! They essentially farm bacteria on their pincers. They feed on that bacteria, and the bacteria feed on sulfur emerging from beneath the earth’s crust. So scientists believe they are dancing and waving their pincers around to agitate the sulfur in the water to better feed that bacteria. But it really appears that they are just partying! I actually had the opportunity to see it for myself while diving in the deep-sea research submarine Alvin and it’s just incredible. Everywhere you look you see these furry white pincers waving. They look like they are having the best time!

What advice/tips would you give people of all ages interested in going into an art career that also encompasses science and ocean conservation?

I think that a depth of understanding of your subject makes the art and the science behind it so much more impactful. So if you want to make art about science and/or the ocean, really dig into your subjects. Dedicate yourself to them.

If you were a deep-sea creature, what would you be and why?

I would absolutely be a dancing yeti crab. I love to dance!